From Folk Motifs to Modern Installations: 7 Ukrainian Women Who Redefined Art

Ukraine's rich cultural tapestry has long been woven with vibrant folk traditions and visual motifs. Over the last century, remarkable Ukrainian women artists have taken these roots and transformed them into groundbreaking art forms, shaping not only the national but also the global art scene. From folk-inspired paintings to contemporary installations, these seven women exemplify the dynamic evolution of Ukrainian art.

Sonia Delaunay (1885–1979) — The Pioneer of Orphism and Color Theory

Sonia Delaunay wearing Casa Sonia creations, Madrid, c.1918-20 © Museo Thyssen

Born in Odesa, Ukraine, Sonia Delaunay redefined what it meant to be a modern artist in the 20th century. She emerged in Paris as one of the most audacious colorists of her generation. Together with her husband, Robert Delaunay, she founded Orphism — a movement that broke from Cubism through its lyrical use of color and rhythm. Her creations blurred the line between fashion and fine art, with simple silhouettes brought to life by fearless color juxtapositions and rhythmic abstractions.

Sonia’s textiles were in high demand — from the Lyon silk houses to Liberty of London. She designed theater costumes for dadaist productions and even customized a Citroën car model. Her abstract scarves, dresses, and swimwear turned heads across Europe, culminating in a dress that made the painted cover of British Vogue in 1925, illustrated by the renowned Jean Lepape.

Trois femmes, forms, couleurs (Three Women, Forms, Colours), 1925 © Museo Thyssen

Her painting Trois femmes, formes, couleurs (1925) embodies the essence of Orphism. The canvas pulses with movement, layering geometric shapes and pure tones to create a harmony of motion and emotion. The three female figures are almost dissolved into the interplay of forms, cubes, and diagonals, reflecting not individual portraiture but the collective rhythm of modern life.

In all her endeavors, Sonia remained true to her foundational vision: color as movement, form as music, and art as life. Her Orphist designs weren’t merely aesthetic—they were philosophical, infused with the dynamism of modernity and the memory of folk heritage.

In 1964, at age 79, Sonia Delaunay became the first living woman artist to have a solo exhibition at the Louvre. The retrospective presented 177 works, which she later donated to the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris. Her legacy continued to grow, honored by the Grand Prix of the Cannes International Exhibition, the Legion of Honor, and the Gold Medal of the City of Paris.

Olexandra Exter (1882–1949) — The Visionary of Cubo-Futurism and Theatre Design

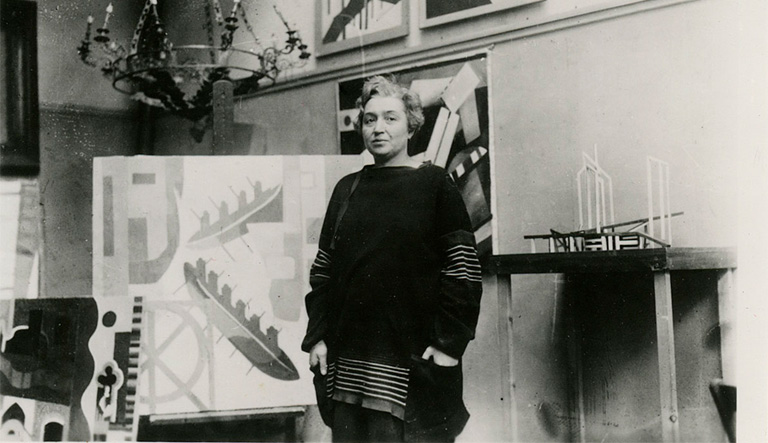

Olexandra Exter in her studio in Paris © Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

Olexandra Exter stands as a seminal figure in the European avant-garde with Ukrainian cultural identity. Her contribution extended beyond the canvas. As a pioneering scenographer, Exter revolutionized theatrical design with kinetic, abstract sets that turned performance spaces into immersive modernist environments. Her stage works for Romeo and Juliet, Salomé, and Faust rejected illusionism in favor of geometry, volume, and color in motion — effectively reshaping theatre’s visual grammar.

After emigrating to France in the 1920s, Exter became a sought-after teacher in Parisian art schools. Although often claimed by Russia, Exter is firmly rooted in the Ukrainian avant-garde. Like Kazimir Malevich — himself born in Kyiv and profoundly shaped by Ukrainian culture — Exter is part of the same intellectual milieu. Yet their legacies, often misattributed or uprooted, are intrinsically tied to Ukraine’s modernist awakening.

Kubo-Futuristische Komposition (Hafen), between 1912 and 1914 © Raimond Spekking

While deeply involved in Cubism and Futurism, her work consistently transcended these schools. Her painting Kubo-Futuristische Komposition (Hafen) — likely created between 1912 and 1914 — exemplifies this synthesis. In this composition, Exter turns a harbor scene into a vibrating structure of intersecting planes, fractured perspectives, and luminous color contrasts. The urban dynamism of the port — with cranes, ships, and industrial silhouettes — becomes a kind of rhythmic abstraction, echoing the pulse of modernity.

This painting is not just a representation of a place; it’s a vision of the new world Exter believed in — one shaped by movement, transformation, and the fusion of local roots with global currents.

Maria Prymachenko (1909–1997) — The Naïve Art Icon

Maria Prymachenko. Photo from open sources

Maria Prymachenko’s works are deeply rooted in Ukrainian folk culture, known for their vibrant colors, fantastical animals, and symbolic motifs. She was a self-taught artist who created over 800 paintings.

Although Prymachenko spent her entire life in the village of Bolotnia in the Kyiv region and never traveled abroad, her art gained international recognition and continues to captivate audiences with its unique “naïve” style. Her paintings have been exhibited in many cities around the world.

Prymachenko transformed local myths, dreams, and fears into vibrant allegories through her distinctive style — a fusion of neo-primitivism, naïve art, and deep-rooted folk tradition. She is best known for her depictions of fantastical creatures, each with its distinct personality. Her beasts are protectors, victims, rebels, prophets. They are stitched from fear, satire, wonder, and defiance. Through them, Prymachenko commented on war, ecology, spirituality, and humanity with a voice both universal and deeply Ukrainian.

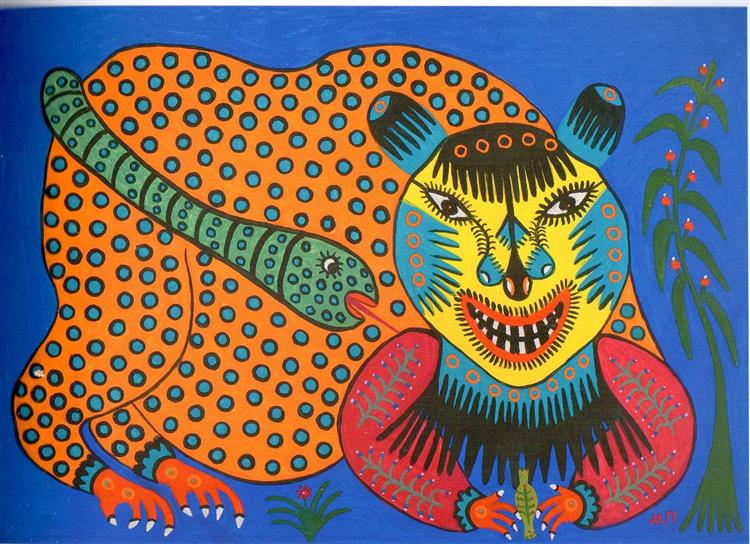

While This Beast Drinks Poison, a Snake Sucks His Blood, 1982 © Maria Prymachenko

Her painting While This Beast Drinks Poison, a Snake Sucks His Blood (1982) is a prime example of her symbolic, allegorical language. In this image, a bizarre hybrid beast — equal parts feline, canine, and bird — crouches as it drinks poison, unaware (or resigned) to the fact that a serpent coils around it, simultaneously draining its blood.

This scene, like many of Prymachenko’s works, operates on multiple levels. On the surface, it is a folkloric fable — the kind of story whispered in villages to warn or instruct. But beneath this lies a sharp moral and political allegory. Created during the final decade of the Soviet Union, the painting can be interpreted as a metaphor for self-destruction and parasitism: a warning about the toxic cycles of power, the dangers of ignorance, or the internal collapse of an unjust system.

Tragically, some of Prymachenko’s works were lost when the Ivankiv Museum was destroyed by Russian forces — I mentioned this earlier in the article "Ukrainian Art & Culture at Risk: Frontline Evacuations and Preservation Efforts". At the time, local residents managed to save 14 of her paintings.

Kateryna Bilokur (1900–1961) — The Master of Ukrainian Floral Imagery

Kateryna Bilokur © Encyclopedia of Modern Ukraine

Kateryna Bilokur’s art is also rooted in the soil of her native Ukrainian village. Without formal education or artistic training, she became a self-taught genius. Denied access to formal education, she studied the world through her garden and fields, rendering peonies, poppies, cornflowers, and ears of wheat with astonishing precision and emotional intensity.

Living in Bohdanivka, a small village in the Kyiv region, Bilokur endured the crushing realities of 20th-century Ukrainian history: the Revolution, the Holodomor, Nazi occupation, and Soviet repression. Through it all, she remained committed to her passion — painting. In doing so, she waged a silent rebellion against both the patriarchal attitudes of her family and the ideological confines of her times.

Bilokur’s works reflect a deep fusion of Ukrainian folk tradition and a personal, almost mystical, perception of nature. The flowers in the paintings seem to float in the air, glowing with an inner light that speaks of spiritual transcendence and quiet defiance. Her famous painting Wildflowers (1940) exemplifies this approach: every petal and stem is meticulously painted, creating a composition that is both naturalistic and visionary, intimate yet monumental.

Wildflowers, 1940 © National Museum of Decorative Arts of Ukraine

The story of her recognition is as remarkable as her art. In 1949, she was admitted to the Union of Artists of Ukraine. Her works were exhibited in Kyiv and Moscow, although often under the condescending label of “peasant artist”. Soviet propaganda framed her as a symbol of the ideal kolkhoz worker's “happy life,” ignoring her complex inner world and profound artistic ambition.

Though she never left her village and died without ever holding a passport, Kateryna Bilokur left behind a body of work that situates her among the most extraordinary artists of the 20th century. In 1954, her paintings were featured in the Soviet pavilion at the International Exhibition in Paris. It was there that Pablo Picasso allegedly saw her works and exclaimed, “If we had a painter of this level of mastery, we would make the whole world speak of her”.

Alla Horska (1929–1970) — The Dissident Artist and Human Rights Activist

Alla Horska © Ukrainian Art Library

Alla Horska was not born into Ukrainian culture — she chose it. Born into a privileged Soviet family, she made a deliberate turn away from the official ideology and became one of the most powerful figures in Ukraine’s dissident movement. Despite having trained in the traditions of socialist realism, she used that very language to subvert official narratives and preserve Ukrainian identity. A leading figure of the 1960s shistdesiatnyky (Sixtiers) movement, Horska used her art as a platform to confront the Soviet regime’s crimes and advocate for cultural and historical truth.

One of her most powerful — and tragic — artistic gestures was the 1963 stained glass window she created for the vestibule of Kyiv University's Red Building. Alongside fellow artists Opanas Zalyvakha, Lyudmyla Semikina, Halyna Sevruk, and Halyna Zubchenko, Horska designed a bold tribute to Taras Shevchenko, whose figure stood in the center, embracing a symbolic Ukraine-mother with one arm and fending off oppressors with the other. Above the image was an inscription: "I shall exalt those little mute slaves; I shall place the word as a watchman by them!"

Sketch of the stained glass window "Shevchenko. Mother" for Kyiv University, 1964 © Alla Horska

Though officially approved in sketches, the composition triggered outrage among Soviet authorities. It was declared “formalist and hostile.” Instead of being unveiled, the completed stained glass window was smashed to pieces.

Horska was expelled from the Union of Artists, and under constant surveillance, she continued her advocacy until her sudden and violent death in 1970. Found murdered with an axe blow to the head, her case remains unsolved, yet widely believed to be politically motivated. She was only 41.

Her mosaics — Tree of Life and Boryviter (Kestrel) — once gracing the urban landscape of Mariupol, were deliberately destroyed by Russian troops during the 2022 invasion.

Oksana Mas (b. 1969) — The Contemporary Visionary of Installation Art

Oksana Mas © Facebook Mas-Art

Oksana Mas is an artist whose work blends folklore, religious symbolism, and cutting-edge technology to create emotional experiences. Her visual language offers a reimagined conversation between tradition and modernity.

Working across painting, sculpture, digital art, and monumental installations, Mas sees art as a bridge — not only between past and future, but also across social, religious, and national divides. Her works invite reflection on shared memory and identity, often transforming personal experiences into collective rituals. This ethos is central to her most iconic and ambitious project: Altar of Nations.

Installation of the "Altar of Nations" project in Kyiv on Sofiivska Square, 2012, Kyiv, Ukraine © 2024 OKSANA MAS

At the 54th Venice Biennale in 2011, Mas unveiled a part of "Altar" – Post vs. Proto Renaissance – a monumental, evolving work inspired by the Ghent Altarpiece. It is composed of 400,000 hand-painted wooden Easter eggs. In an act of participatory art, Mas invited people from across the world to contribute their inner worlds to the piece, turning the work into a living archive of humanity’s emotional and spiritual complexity. Critics and curators at the Biennale hailed the project as the largest and most ambitious of the festival, noting its power to unify diverse spiritual traditions under a single aesthetic gesture.

Beyond Venice, Mas has showcased her work at the major international art fairs, including Art Basel Miami, Frieze London, FIAC Paris, ARCOmadrid, and The Armory Show in New York. Her pieces have entered prestigious collections, including sales at Sotheby’s and Christie’s.

400,000 wooden eggs

Zhanna Kadyrova (b. 1981) — The Artist with Concrete and Tiles

Zhanna Kadyrova © Secondary Archive

Zhanna Kadyrova transforms the language of sculpture by using urban materials — concrete, tiles, and fragments of architectural elements. Her works blur the boundaries between industrial waste and cultural memory, referencing traditional Ukrainian motifs through the most unexpected of mediums. By creating different forms from concrete or reimagining city structures, she speaks to the connection between past and future, collapse and resilience.

Kadyrova’s practice is deeply site-specific: she creates sculptures, mosaics, installations, and performances that respond to the social, historical, and political realities of their surroundings. Whether in the streets of Kyiv or international exhibition spaces, her works investigate the relationships between place, people, and memory. Her artistic voice has become loud in contemporary Ukrainian art, with multiple appearances at the Venice Biennale — including representing Ukraine at the 55th and 56th editions, and as a featured artist in the 57th.

Palianytsia, 2022, Venice, Italy

One of her most poignant recent works emerged from the war itself. In 2022, while living as a displaced person in western Ukraine, Kadyrova launched the Palianytsia project. The project is named after the Ukrainian word for a traditional round loaf of bread, which, due to its pronunciation, became a wartime shibboleth – a symbol of resistance and cultural identity that Russian occupiers could not mimic. Kadyrova began collecting smooth river stones in the Carpathians and painting them to resemble loaves of bread, transforming hard, unyielding material into symbols of warmth, survival, and national unity.

Anastasiia Stepanenko, grant writer, project manager, cultural critic, expert at the United Ukraine Think Tank