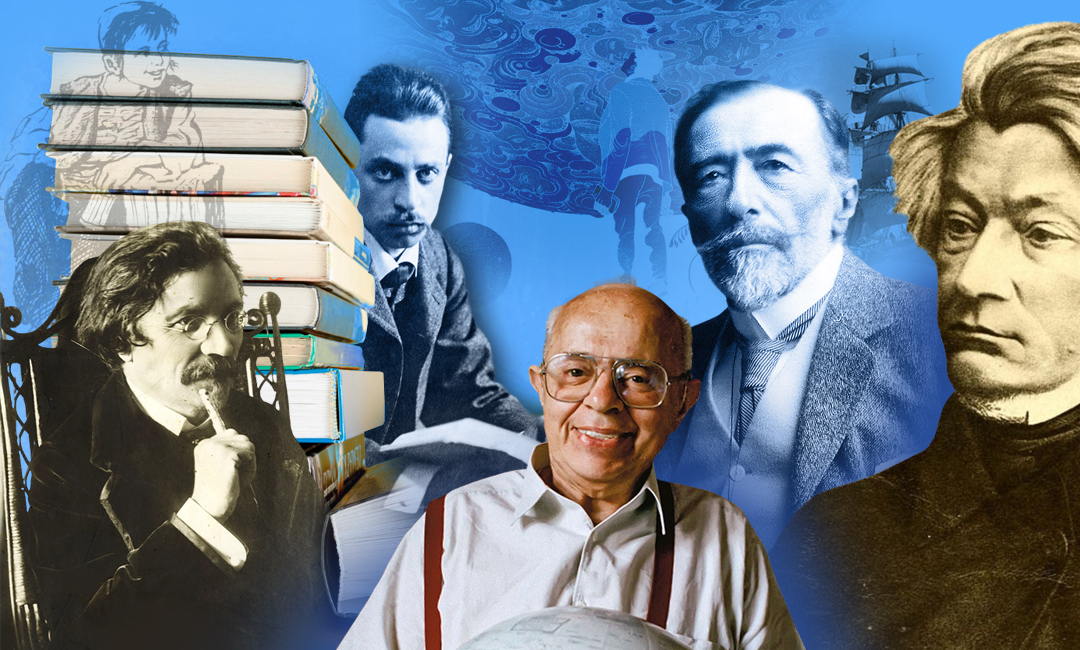

Five Writers from Other Cultures Born and Connected to Ukraine

For centuries, Ukraine has stood at the crossroads of empires, languages, and identities—a place where cultural influences collided, intertwined, and left lasting marks. For some of the world’s most celebrated writers, Ukraine was a birthplace, a formative landscape, or a fleeting yet unforgettable stop in their journeys. Their work has reached global heights, but somewhere in their stories—overtly or subtly—Ukraine speaks.

Here are five literary figures from beyond Ukraine’s borders whose work was influenced by Ukraine and who influenced world literature.

Joseph Conrad (1857 – 1924)

Though remembered today as one of the great novelists and story writers of English literature, Joseph Conrad was born in 1857 in Berdychiv, a multicultural town in what is now central Ukraine. He was raised in a Polish noble family under the repressive rule of the Russian Empire. His father, Apollo, was a poet and revolutionary who was exiled in 1861 by the Tsarist authorities—a fate that forced the family into a nomadic and unstable existence.

Conrad's earliest memories were formed amid the layered languages and loyalties of the Ukrainian frontier, where Polish resistance, Russian control, and Jewish and Ukrainian communities coexisted in tension. This multicultural environment introduced him, even as a child, to the fragile borders of identity, which would become a central theme in his fiction.

That early dislocation, along with the charged atmosphere of the imperial borderlands, left a permanent imprint on Conrad’s inner world. Though he eventually wrote in English and became best known for novels like Heart of Darkness and Lord Jim, the emotional landscape of his childhood, a life lived between languages, cultures, and empires, resurfaced throughout his writing.

In "A Personal Record", Conrad recalled Ukraine as his "first country," the place where he formed his earliest impressions of life, people, and language. Themes of exile, statelessness, and dislocated identity reappear in works like Youth and The Shadow-Line, in which protagonists wrestle with isolation and memory, not unlike the young boy who left Berdychiv and never returned but never let it go.

Sholem Aleichem (1859 – 1916)

Sholem Aleichem (born Solomon Rabinovich, 1859–1916) spent most of his life in what is now Ukraine—in cities and towns such as Pereiaslav, Kyiv, Lubny, Boyarka, Odesa, and briefly Lviv. Often referred to as the “Jewish Mark Twain,” he became the most beloved voice in modern Yiddish literature, capturing with both humor and heartbreak the daily realities of Jewish life in Eastern Europe.

His fictional universe was rooted in the Ukrainian shtetl, and his characters, from the philosophical Tevye the Dairyman to the hapless dreamer Menakhem-Mendl, speak from a world shaped by pogroms, poverty, hope, and migration. The Tevye stories (1894–1914), which later inspired Fiddler on the Roof, unfold against the backdrop of Ukrainian villages and echo the moral and emotional dilemmas of a people caught in historical upheaval.

Between 1887–1890, 1893–1905, Aleichem lived for long stretches in Kyiv, which he thinly veiled in fiction as “Yehupets.” In Odesa, where he moved in 1891, he entered the city’s vibrant Jewish literary scene, collaborated with writers like Mendele Mocher Sforim, and launched publishing ventures like the Yidishe Folksbibliotek (Jewish People’s Library). The city also inspired some of his finest work, including Menakhem-Mendl, parts of which first appeared in the local press. Though financial struggles and anti-Jewish violence eventually drove him from Odesa, the experience marked a second major phase in his literary career.

In the early 1900s, he briefly relocated to Lviv. There, he discovered a dramatically different Jewish reality—one shaped by civil freedoms and cultural autonomy. He was impressed by Lviv’s Jewish institutions, its many synagogues, and especially its Yiddish theater, where he became involved with directors and artists. The pluralistic atmosphere of the city, where Ukrainians, Poles, and Jews lived side by side, left a lasting impression on him.

Even after emigrating to New York, Ukraine remained his emotional homeland. In his letters, he referred to Boyarka near Kyiv as his “paradise lost.” Through his characters, cadences, and unmistakably Ukrainian settings, Sholem Aleichem preserved a world now vanished—a world of laughter, exile, and memory.

Rainer Maria Rilke (1875 – 1926)

Unlike Conrad or Aleichem, Rainer Maria Rilke was not born in Ukraine, but his travels there in 1900–1901 left a lasting mark on his poetic vision. Invited by Princess Maria von Thurn und Taxis, and accompanied by his muse Lou Andreas-Salomé, Rilke journeyed through Kyiv, Poltava, Kharkiv, and the wide-open steppe—encountering a landscape and spiritual atmosphere unlike anything he had known before.

Rilke arrived in Kyiv in May 1900 and continued his journey through central and eastern Ukraine over the summer months. He attended Orthodox services, visited monasteries, and closely observed village life. Ukraine offered Rilke not just inspiration but a sense of spiritual grounding. In his letters, he frequently reflected on the region’s unique rhythm of life—slow, contemplative, and steeped in centuries-old ritual—which contrasted sharply with the industrial bustle of Western Europe.

Though he never named Ukraine explicitly in his poetry, the vast silence of the plains, the candle-lit Orthodox churches, and the sense of deep time filtered into his writing, particularly in The Book of Hours (Das Stunden-Buch), written between 1899 and 1903. The section titled “The Book of a Monk’s Life” is filled with the kind of mystical stillness and sacred minimalism that he found in Ukrainian monasteries and rural villages.

In a letter from Poltava, Rilke wrote of golden domes shining under a heavy sky and described the silence not as emptiness, but as presence. That paradox of space as spiritual fullness became central to his later works, such as The Duino Elegies and Sonnets to Orpheus. His time in Ukraine offered him not just a new landscape, but a new vocabulary for the soul.

Adam Mickiewicz (1798 – 1855)

For Adam Mickiewicz, Ukraine was more than a place on the map—it was a landscape of the soul. Though born in what is now Belarus, the Polish Romantic poet found in Ukraine a space that symbolized freedom, wild beauty, and cultural depth. His time spent in Kyiv, Odesa, Kamianets-Podilskyi, and Crimea during the 1820s left a lasting imprint on his imagination. Exiled by Russian authorities, Mickiewicz encountered Ukraine as a source of myth, memory, and poetic energy. The Ukrainian steppe, in particular, captivated him—its openness symbolized both physical freedom and psychological release. For Mickiewicz, Ukraine became a space where the past could be reimagined and national identity reasserted through legend and lyricism.

He immersed himself in Ukrainian folklore, drew inspiration from Cossack legends, and cultivated relationships with local intellectuals. The vast steppes, Orthodox spirituality, and historical echoes he encountered infused his poetry with rich symbolism. His celebrated Crimean Sonnets (Sonety Krymskie), composed between 1825 and 1826, form a poetic cycle that weaves together elements of travel narrative and spiritual reflection. They marked one of the earliest European literary attempts to frame Crimea not just as a picturesque setting but as a zone of spiritual and civilizational encounter. Though set in Crimea, the work captures a broader fascination with the Eastern frontier, depicting the region as both mysterious and liberating.

Ukrainian themes also ripple through his epics Konrad Wallenrod and Pan Tadeusz, where borderland nobility, Cossack figures, and references to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth’s eastern territories reflect a shared cultural and historical landscape. For generations of Polish readers, Mickiewicz’s writings helped shape the image of Ukraine as a romanticized, semi-mythical homeland — a place of both loss and creative rebirth. Today, his legacy is embraced not only in Poland, but also in Ukraine and Eastern Europe as part of a shared, entangled literary heritage.

Stanisław Lem (1921 – 2006)

Long before Stanisław Lem became one of the most influential science fiction writers of the 20th century, he was a curious boy wandering the streets of Lviv—a city of many languages, faiths, and ideas. Lem grew up surrounded by Polish, Ukrainian, Jewish, and Armenian cultures, all layered within the intricate urban fabric of Galicia. His father was a physician, and Lem began medical studies at Lviv University, but his education—like the city itself—was disrupted by the twin traumas of Soviet and Nazi occupation. The war interrupted his studies and forced him to work as a mechanic and welder, experiences that later influenced the detailed technical imagination in his speculative fiction.

Those early years in Lviv, filled with both intellectual energy and existential dread, would echo throughout Lem’s literary universe. In Highcastle: A Remembrance (Wysoki Zamek), one of his rare autobiographical works, Lem looks back on his childhood with warmth and clarity, recalling his obsessions with machines, books, and imagination, and painting a vivid picture of a city on the edge of history. The High Castle hill, a ruined fortress overlooking Lviv, becomes both a literal and symbolic high ground—a site of memory, wonder, and personal mythology. His descriptions of Lviv are analytical and layered, capturing the city’s ambiguities, its multilingual street life, and its fractured memory landscape.

Although Lem rarely wrote explicitly about Ukraine in his fiction, the absurdity of bureaucracy, the instability of truth, and the alienation of the individual—all recurring themes in his novels—reflect his formative experiences in a region where ideology often overpowered reality. In works like Solaris, The Cyberiad, and Memoirs Found in a Bathtub, we find a writer grappling with the limits of human knowledge and the incomprehensibility of the universe — questions born, in part, from witnessing the chaos and cruelty of totalitarian systems. In later interviews, Lem acknowledged that his skepticism toward authority and ideology was shaped by witnessing the shifting occupations and moral disorientation of his youth in Lviv.

Stanisław Lem resettled in Kraków in 1946, after the end of World War II, never returning to Lviv, which had become part of Soviet Ukraine. Yet the city remained with him—a kind of lost Atlantis, rich in contradictions, and central to his intellectual development. Though firmly established in the canon of Polish literature, Lem’s roots in Ukrainian Galicia—with all its complexity, fragility, and brilliance—continue to shape how we read his work today.

These five writers — from different cultures, writing in different languages — are bound by a shared thread: Ukraine. For some, it was home; for others, it was a place of exile, inspiration, or transformation. Whether through the wry humor of a Jewish dairyman, the mystical solitude of a wandering poet, or the philosophical meditations of a science fiction visionary, the landscapes, memories, and tensions of Ukraine ripple through their works.

In retracing these literary footprints, we see Ukraine not as a blank space between empires, but as a cultural force of its own — complex, generative, and deeply woven into the fabric of global literature.

Anastasiia Stepanenko, grant writer, project manager, cultural critic, expert at the United Ukraine Think Tank